SEPTEMBER 2 – OCTOBER 1

Olga Kisseleva (born 1965) is one of the key figures within science-art, an international genre that activates bodies of scientific knowledge and technology within the sphere of art. The artist currently serves as a professor at the Sorbonne and the director of the International Institute of Art and Science. Kisseleva’s practice draws from exact sciences, biogenetics, and geophysics, as well as from political and social sciences. The artist conducts scientific experiments, producing calculations and analyses of her findings, all in strict observance of the methods and protocols adopted in the respective scientific fields. In other words, she applies a purely scientific method to test and confirm her artistic hypotheses.

Kisseleva's installation for ZARYA CCA is dedicated to the phenomenon of nets. As we know, nets are some of the primary means for catching aquatic bioresources – a theme of particular relevance for Vladivostok, one of the centers of the world's fishing industry. And although the use of nets in amateur fishing in Russia is currently restricted by law, and thus very few people can take advantage of this simple and yet extremely effective tool, the net thrives as a universal symbol with many possible applications and analogies.

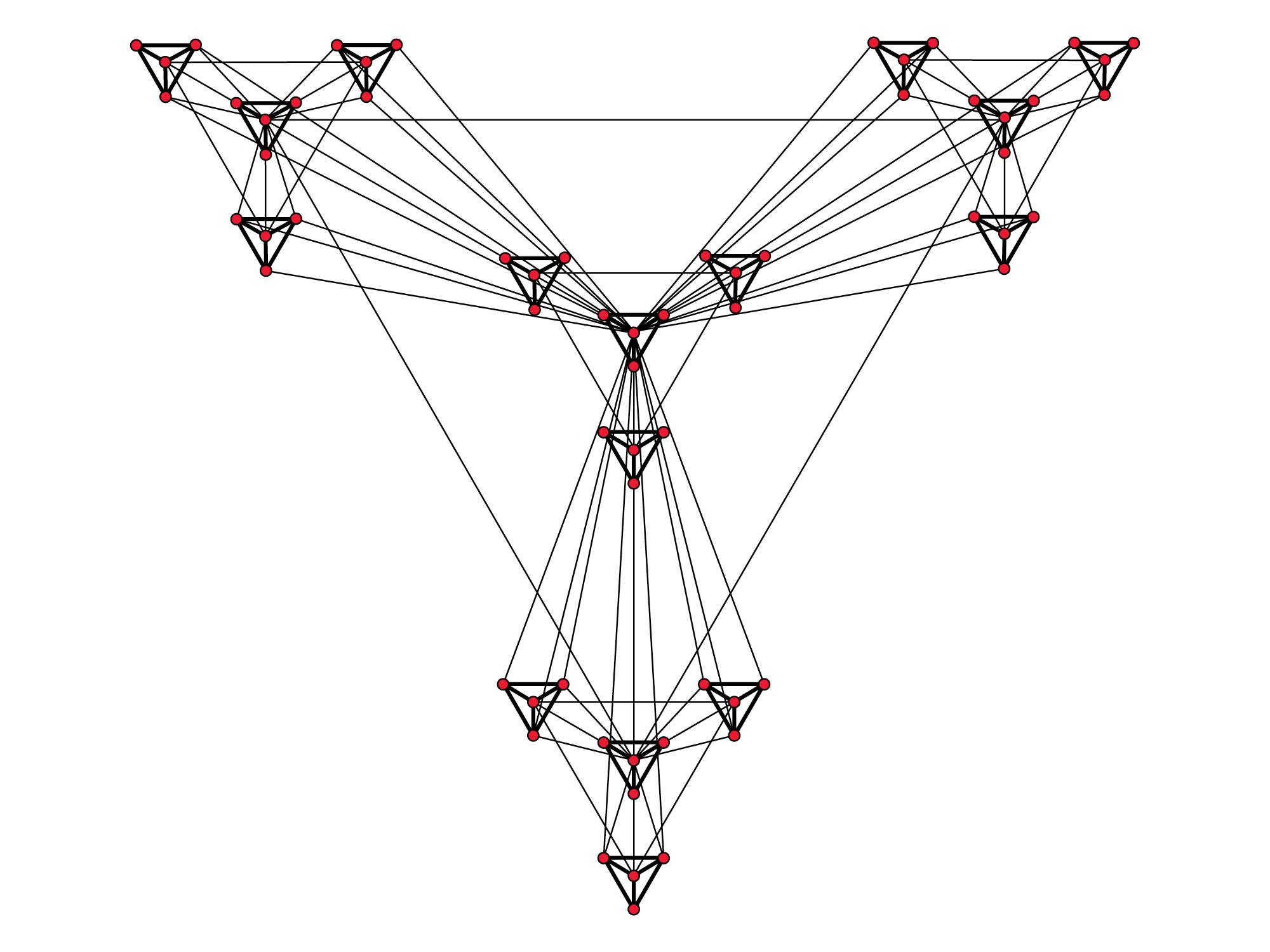

In Russian language, the word “net” – set’ – can refer to fishing nets or computer and social networks, but it can also be used to describe the linking of various systems related to commercial, transport, or industrial interests. Comparing the form of these structures – starkly different in terms of both implementation and purpose – one can uncover a series of similarities. For instance, in computer and social networks, as well as in hunting nets, one finds nodes that can perform the role of both the connections that link the elements and the center that determines the functioning of each of these systems. Moreover, in some instances, the structure of computer network, with its connections, branches, nodes, cells and clusters, almost entirely replicates the structure of a fishing net.

The invention of each of these types of nets marked an important step in the development of civilization. For example, when fishing tackle first appeared several thousand years ago, it helped improve methods for obtaining food in societies, giving rise to an agglomerating type of economy. Truly a universal tool, these nets could be found among people’s living in vastly different corners of the world. In turn, the social networks so firmly ingrained in modern society provide not only a means of communication between individuals, but also a powerful instrument for marketing research, channels for the distribution of information, and a barometer for the transformation of social roles. The development of these online networks has become synonymous with the idea of progress in the field of computer technology and telecommunications. Computer networks can also be seen as a means of transmitting information across great distances, a process that involves the coding and multiplexing of data.

However, even if you take into account the indisputable use value of any type of network, the semantic content of the term itself can carry both positive and negative associations. After all, a net is something originally designed to capture and contain its victim – a concept borrowed first and foremost from the net’s naturally-occurring prototype, the spider web. For fish, slipping into a net is a sign of certain death; for people, “entanglement” within various technological networks is something intrinsically associated with the subliminal threat to one’s freedom, the threat of becoming dependent.

And yet, today, in the fields of communications and green energy, we see more and more a direct use of technologies that have been closely modeled after the fishing net. For example, the recent proposal for ridding the oceans of plastic waste, developed by an order from the European Union, is based on an interactive system that imitates fishing nets, piloted through the Internet. The plastic harvested from the ocean (now mixed with elements of the marine biosphere) can be used as a raw material for the production of a new type of bio-fuel, a prototype of which has already been created. In this sense, a deep understanding of the structures and functions of an instrument as ancient and basic as a fishing net can factor into predictions for new methods of functioning in the global society of the future, in which everything is interconnected – The Connected World.

Olga Kisseleva’s project, Net (Work), was developed in close collaboration with computer technology experts, alongside fishermen and specialists in the field of production of equipment for the fishing industry. Comparative research was conducted along the Atlantic and Mediterranean shores of France and the Pacific coast of Vladivostok. The project will continue in the form of academic, social and technological developments towards proposing new forms and new functions for the net.

This exhibition additionally offers a chance to explore the artist’s previous work, through an interactive presentation.