Yana Gaponenko, Inna Dodiomova, Roman Ivanischev, Kristina Norman, Aleksei Taruts, Ksenia Frolova; John Craig Freeman, Melissa Shiff & Louis Kaplan

Curated by Maria Kramar

The exhibition Absent Monuments develops on a curatorial project that started while in residence at Zarya CCA in 2015, when research into the local context, conducted alongside students of a month-long training course, sparked an interest in the idea of “nonmaterial monuments.”

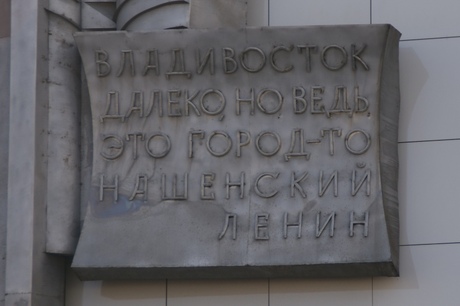

Absent Monuments explores the material forms of memory existing today in the nonmaterial landscape of Vladivostok.

This line of thinking departs from the paper monument of the Colossus of Rhodes, the Ancient Greeks’ giant sculpture of the sun god, Helios, which – purportedly – stood guard over the port city of Rhodes. To this day, it remains authoritatively ranked as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and yet there is no evidence of the actual physical existence of the monument. Moreover, we know neither the form, nor the exact location of the statue. The only available evidence of its existence – works of literature and fantasy paintings – are as credible a source as Ancient Greek mythology. Rather fascinatingly, in 2008, several different companies suddenly expressed an interest in reconstructing the sculpture, be it as a light installation or a mall.

Such utopian approach is quite typical for visionary architecture, a concept embodied not so much by the avant-garde projects of the Soviet architects of the 1980s, as by the negative monuments of Giovanni Battista Piranesi. The 18th century Italian architect produced countless etchings depicting imaginary landmarks, the capitals of columns on ancient buildings, sculptural fragments, sarcophagi, stone vases, candelabras, pavement tiles, tombstone inscriptions, architectural layouts, cityscapes, and more, though in his lifetime, he only ever erected one completed building. As Piranesi famously wrote, “They despise my novelty and humble birth, I their cowardly conservatism.”

However, one defining feature of visionary architecture is its default unbuildable function. Thus, the “paper” function is built-in from the start, allowing authors to embrace the technical complexity, scale, idealistic, utopian notion, and exorbitant costs of their projects. On the contrary, in our case, the lack of realization / death of a monument is spontaneous or unplanned quality / event, rather than intended.

The monument to Russian Navy Admiral Vasily Zavoyko, which was demolished and replaced by a statue of Bolshevik leader Sergey Lazo. Zurab Tsereteli’s plans to erect the world’s largest statue of Jesus Christ. A proposed memorial to whalers. The dismantled monument to Admiral Gennady Nevelskoy. Augmented reality Ararat memorial. The U.F.O. memorial in Estonia. What all of these episodes share is a common interest in addressing a memory that cannot be accessed through any other means? Is it possible for a monument – generally a massive object, containing historical – to function in an ephemeral environment, such as text, visual images, sound, or even smartphone apps? In such forms, could it still continue to serve as a repository for memory?

The curator and participants in this project will rely upon a two-way process – both the commemoration/de-commemoration and the absence/interruption of monuments – to start a discussion on the city’s historical heritage.

The exhibition will present art works alongside archival documents, photographs, and found videos, as well as commentary by historians, archivists and sculptors.