SEPTEMBER 24 – NOVEMBER 12 2017

What attaches to what? Is Venus attached to the seashell, or the seashell to Venus? The East to the West, or the West to the East? The picture to the viewer, or the viewer to the picture?

One could spend hours mapping out the system of hierarchies governing the relationships between objects and other phenomena, but what would be the point? It’s more important to observe how all of these relationships interact, according to their own free-form logic, impervious to any guiding rationale. We do not ask the viewers to understand this exhibition. If anything, it actually might be better NOT to understand it, in keeping with the way of Taoists, who follow the wu wei.

In short, we ask not for understanding, but for love!

EliKuka group announced itself among the art scene in 2007. The members of EliKuka made a number of personal projects in Moscow, Paris and Vienna, they took part in group shows in Russia and abroad. In 2011-2013 they made a series of interactive kinetic installations where the usual rules of behavior

are broken: audience is offered to touch and move the works of art, to arrange the composition at its own and sole discretion. Continuing experimenting, developing the idea of direct mutual influence between the viewer and the piece of art the artists realized the project Propaganda of Photography: the artists’ works became a background for the ones who wanted to take a photo. The group worked in collaboration with artists: Georgy Litichevsky, Valery Chtak, art-group gelitin

(Austria), and others. Also they are members of Moscow punk band I.H.N.A.B.T.B., international musical-artistic formation ANUSRIOT and music band Jenya Kukoverov.

SEPTEMBER 2 – OCTOBER 1

Olga Kisseleva (born 1965) is one of the key figures within science-art, an international genre that activates bodies of scientific knowledge and technology within the sphere of art. The artist currently serves as a professor at the Sorbonne and the director of the International Institute of Art and Science. Kisseleva’s practice draws from exact sciences, biogenetics, and geophysics, as well as from political and social sciences. The artist conducts scientific experiments, producing calculations and analyses of her findings, all in strict observance of the methods and protocols adopted in the respective scientific fields. In other words, she applies a purely scientific method to test and confirm her artistic hypotheses.

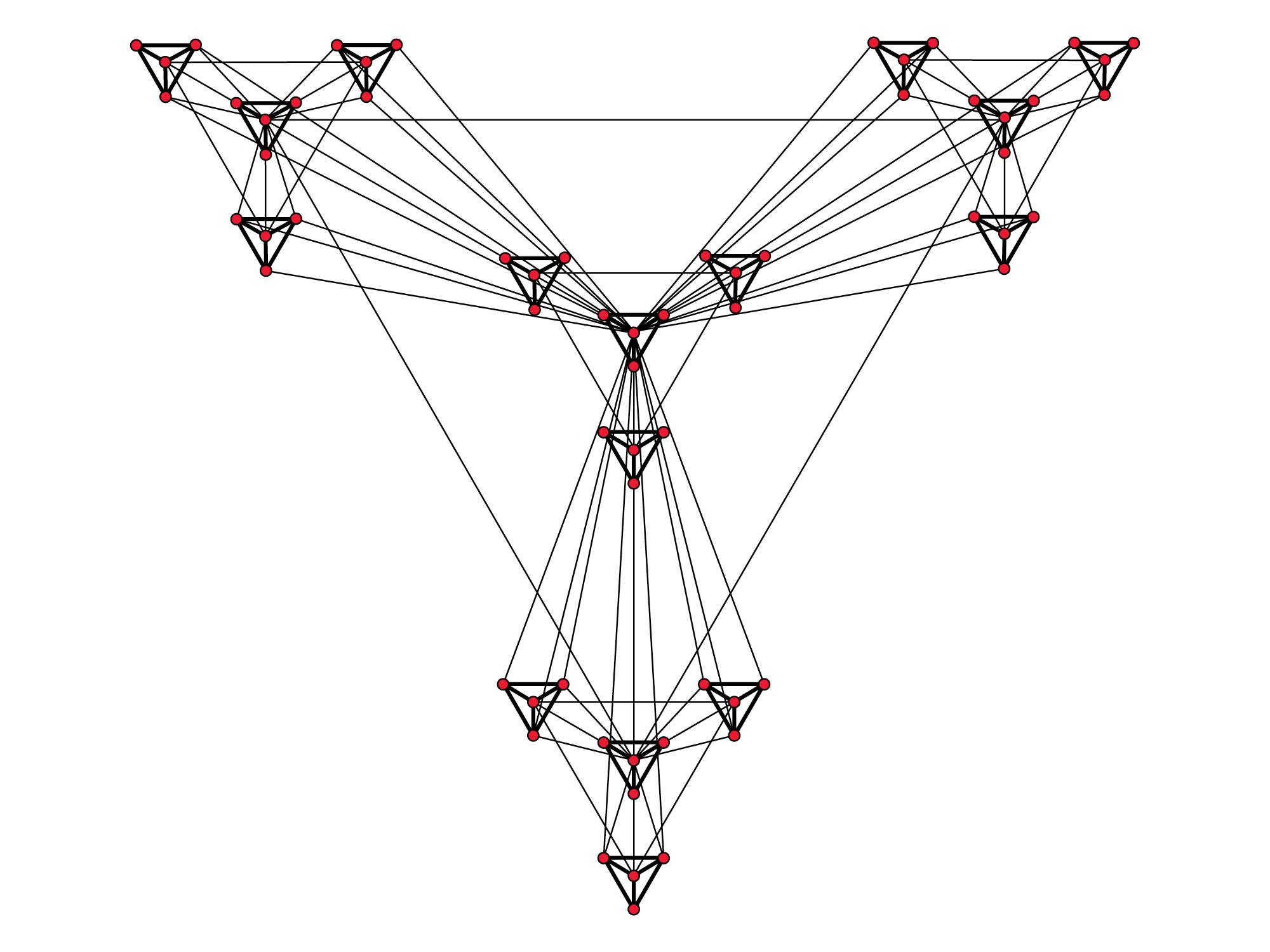

Kisseleva's installation for ZARYA CCA is dedicated to the phenomenon of nets. As we know, nets are some of the primary means for catching aquatic bioresources – a theme of particular relevance for Vladivostok, one of the centers of the world's fishing industry. And although the use of nets in amateur fishing in Russia is currently restricted by law, and thus very few people can take advantage of this simple and yet extremely effective tool, the net thrives as a universal symbol with many possible applications and analogies.

In Russian language, the word “net” – set’ – can refer to fishing nets or computer and social networks, but it can also be used to describe the linking of various systems related to commercial, transport, or industrial interests. Comparing the form of these structures – starkly different in terms of both implementation and purpose – one can uncover a series of similarities. For instance, in computer and social networks, as well as in hunting nets, one finds nodes that can perform the role of both the connections that link the elements and the center that determines the functioning of each of these systems. Moreover, in some instances, the structure of computer network, with its connections, branches, nodes, cells and clusters, almost entirely replicates the structure of a fishing net.

The invention of each of these types of nets marked an important step in the development of civilization. For example, when fishing tackle first appeared several thousand years ago, it helped improve methods for obtaining food in societies, giving rise to an agglomerating type of economy. Truly a universal tool, these nets could be found among people’s living in vastly different corners of the world. In turn, the social networks so firmly ingrained in modern society provide not only a means of communication between individuals, but also a powerful instrument for marketing research, channels for the distribution of information, and a barometer for the transformation of social roles. The development of these online networks has become synonymous with the idea of progress in the field of computer technology and telecommunications. Computer networks can also be seen as a means of transmitting information across great distances, a process that involves the coding and multiplexing of data.

However, even if you take into account the indisputable use value of any type of network, the semantic content of the term itself can carry both positive and negative associations. After all, a net is something originally designed to capture and contain its victim – a concept borrowed first and foremost from the net’s naturally-occurring prototype, the spider web. For fish, slipping into a net is a sign of certain death; for people, “entanglement” within various technological networks is something intrinsically associated with the subliminal threat to one’s freedom, the threat of becoming dependent.

And yet, today, in the fields of communications and green energy, we see more and more a direct use of technologies that have been closely modeled after the fishing net. For example, the recent proposal for ridding the oceans of plastic waste, developed by an order from the European Union, is based on an interactive system that imitates fishing nets, piloted through the Internet. The plastic harvested from the ocean (now mixed with elements of the marine biosphere) can be used as a raw material for the production of a new type of bio-fuel, a prototype of which has already been created. In this sense, a deep understanding of the structures and functions of an instrument as ancient and basic as a fishing net can factor into predictions for new methods of functioning in the global society of the future, in which everything is interconnected – The Connected World.

Olga Kisseleva’s project, Net (Work), was developed in close collaboration with computer technology experts, alongside fishermen and specialists in the field of production of equipment for the fishing industry. Comparative research was conducted along the Atlantic and Mediterranean shores of France and the Pacific coast of Vladivostok. The project will continue in the form of academic, social and technological developments towards proposing new forms and new functions for the net.

This exhibition additionally offers a chance to explore the artist’s previous work, through an interactive presentation.

29 ИЮЛЯ / 13:00—19:00 / ЦЕХ 2, ВХОД 10, ЭТАЖ 1

Благотворительная выставка-раздача кошек по инициативе участника программы арт-резиденции «Заря» Алексея Булдакова и «Лаборатории городской фауны» пройдет на Фабрике «Заря». Все желающие смогут поддержать бездомных кошек, находящихся на попечении волонтерского движения «Спасем жизнь», а также помочь им найти хозяев. Все кошки, участвующие в выставке, подобраны на улице, здоровы и готовы к переезду в домашние условия. Организаторы будут также очень благодарны помощи для животных — любому корму, наполнителю, медикаментам, ветоши.

Инициатором выставки выступил участник программы арт-резиденции «Заря», художник Алексей Булдаков (Москва), который также осуществит художественное оформление выставочного зала. Это событие станет итогом двухмесячного пребывания Булдакова во Владивостоке. Художник является одним из основателей проекта «Лаборатория городской фауны» (совместно с Анастасией Потемкиной, urbanfaunalab.org) и на протяжении нескольких лет изучает животных, населяющих городскую среду, и особенности их взаимоотношений с человеком. В частности, в фокусе его интересов чаще всего оказываются голуби и кошки.

Как известно, кошки сопровождают человека с самых ранних этапов развития цивилизации. Когда с усовершенствованием технологий земледелия появились излишки продуктов, возникла необходимость в их хранении и защите от вредителей, и кошки стали одним из помощников в сохранении запасов урожая. При этом они остаются достаточно независимыми от человека животными. В условиях современных городов кошки продолжают сосуществовать с людьми, часто провоцируя проявления межвидового альтруизма или, в данном случае, заботы представителя одного биологического вида о представителе другого, более слабого. По словам художника, «для городских жителей кошки олицетворяют дикую природу, иррациональную и загадочную. Кормление кошек можно сравнить с ритуальным подношением богам. На выставке все желающие могут принять участие в этом ритуале». Предполагается, что взаимодействие таких далеких друг от друга практик, как современное искусство и волонтерство в защиту животных, сможет способствовать вовлеченности жителей и организаций города в социально значимый процесс благотворительности.

Алексей Булдаков (р. 1980) живет и работает в Москве. Один из основателей проекта «Лаборатория городской фауны» (совместно с Анастасией Потемкиной, urbanfaunalab.org). Изучал искусство и цифровые медиа в Академии Изящных Искусств, Вена (2011-2012), учился в Центре Социальной и Культурной Антропологии РГГУ (1998-2003). Среди персональных выставок - «Городская сауна». Как я научился не беспокоиться и полюбил загрязнение окружающей среды» (ЦСИ «Винзавод», Москва, 2017), «Дарящие надежду» (Галерея XL, Москва, 2016), «Зелень вешняя» (ВДНХ, павильон «Зерно», 2014) и др. Участвовал в таких коллективных выставках, как «New Décor» (МСИ «Гараж», Москва, 2010), «Ударники мобильных образов" (Первая уральская индустриальная биеннале современного искусства, Екатеринбург, 2010), «Футурология / Русские утопии» (МСИ «Гараж», 2010) и др. Его работы находятся во ряде коллекций, включая Государственную Третьяковскую галерею, ГЦСИ, Фонд «Екатерина», Мультимедиа Арт Музей, Москва и др.

Волонтерское движение защиты животных «Спасем жизнь» объединяет активистов Владивостока, помогающих бездомным животным обрести хозяев. На протяжении более чем пяти лет движение регулярно проводит выставки-раздачи на разных площадках города. Подробнее о деятельности движения «Спасем жизнь» можно узнать по телефону +7 (914) 792-54-72 (Лилия).

Вход свободный

.jpg)

21 МАЯ - 4 ИЮНЯ / МАСТЕРСКАЯ АРТ-РЕЗИДЕНЦИИ (ЦРМ, 5 ВХОД)

20 МАЯ / 20:00 / ВЕРНИСАЖ / ПЕРФОРМАНС «РЕЧЬ» / МАСТЕРСКАЯ АРТ-РЕЗИДЕНЦИИ (ЦРМ, 5 ВХОД)

Современный миф, по Ролану Барту, есть форма речи, которая служит, в том числе, для деполитизации, то есть для того, чтобы представить сконструированную кем-то когда-то реальность, в том числе политическую, как нечто само собой разумеющееся. Миф берет факт истории и превращает его в факт природы. Он опорожняет социальную реальность, выпаривает ее. Мифотворчество – важнейшая функция политического субъекта. Задуматься о происхождении мифа – значит поставить под сомнение сложившийся политический порядок. Самому заняться мифотворчеством – значит стать политическим субъектом.

Миф о Владивостоке как советском Сан-Франциско возник после посещения обоих городов Никитой Хрущевым и бытует до сих пор. Хрущев залетел во Владивосток на обратном пути после визитов в Америку и Китай. Письменных источников, подтверждающих, что именно он призвал сделать Владивосток советским Сан-Франциско, который видел за несколько дней до этого своими глазами, не сохранилось. В официальном тексте речи, произнесенной Хрущевым во Владивостоке, ничего такого нет, хотя Америке посвящена бóльшая ее часть. Но для мифа это и не важно: он «работает» на нечетких ассоциациях.

Америка – вечный и неотъемлемый Другой русского политического воображения начиная с XIX века. В истории с возвращением Хрущева из Америки и рассказом владивостокцам о поездке его можно представить отцом семейства, который, съездив в загранку, вернулся с сувенирами и рассказывает детям о впечатлениях. «Дети» подхватывают поверхностное сравнение их города с далеким романтическим Сан-Франциско, и не важно, что по сути это был неосознанный, парадоксальный призыв к подражанию, несмотря на декларируемую непримиримую борьбу с капитализмом и декларируемое превосходство над ним. Советская пропаганда в конце 1950-х только начала превращать Америку в главное внешнеполитическое пугало, свежи еще были воспоминания о союзничестве во Второй мировой войне, а благодаря классической русской литературе эта страна вообще была синонимом чуть ли не земли обетованной. Видимо, хрущевское сравнение удачно легло на подспудную русскую мечту об Америке, а логические и идеологические нестыковки мифу не мешают.

Интересна история локального мифотворчества в самом Сан-Франциско. В 1961 году здесь впервые открытый гей выставил кандидатуру на выборах в городское собрание, в том же году на местном телевидении впервые показали фильм о гей-движении, а уже в 1964-м журнал TIME назвал Сан-Франциско гей-столицей Америки. Именно этот город стал глобальным центром гей-движения и ассоциируется теперь в мире именно с ним. В проекте «Америка» я дополняю владивостокский миф о Сан-Франциско некоторыми деталями, добавляю ему контекста, ведь миф боится именно полноты образа, помещения в контекст, ибо оперирует только фрагментами. Мы «плаваем» в мифах, пóходя выпекаемых политиками, бездумно подхватываем слова, произносимые ими, какими бы пустыми и бессмысленными они ни были, говорим и пишем штампованным языком бюрократии, не осознавая этого, а значит подчинены ей. «Политический язык, – писал Джордж Оруэлл в 1946 году, – предназначен для того, чтобы ложь звучала правдиво, убийство выглядело достойно, а пустословие – солидно». Ему же принадлежат слова: «Если мысль коверкает язык, то и язык может коверкать мысль».

Анализируя в своем сборнике Mythologies (1957) мифы, которые производит буржуазное общество, Ролан Барт кратко остановился и на мифах, которые он назвал «левыми», хотя имел в виду в том числе и мифы советские. Отличие советских «левых» мифов от буржуазных, по мысли Барта, заключается в том, что если буржуазные мифы всеохватны, распространяются на все сферы социальной жизни, то левые – случайны, вымучены, буквальны (в Сан-Франциско пересеченный ландшафт, значит Владивосток похож на Сан-Франциско), они будто созданы по приказу. Если буржуазный миф – это стратегия, то левый – лишь тактика. Причина этого – в природе левой идеологии. Поскольку она определяет себя только по отношению к угнетенным, а язык угнетенных прямолинеен и не способен ко лжи и к производству мифов, то и советское мифотворчество было скудное и ситуативное. Ему не хватало сил, чтобы стать буржуазным, изобрести буржуазный метаязык, который якобы только и способен производить мифы.

Инсталляция «Америка» состоит из нескольких элементов, связанных друг с другом неявным образом: это подлинные открытки Сан-Франциско конца 1950-х гг., купленные у одного владивостокского коллекционера: их можно представить как сувениры, привезенные отцом детям; на них бюрократическим инструментом – штампом – нанесены лозунги о Сан-Франциско и Владивостоке (они имитируют советские и могли быть произнесены Хрущевым); репринт газеты «Правда» от 8 октября 1959 г. с речью Хрущева, произнесенной двумя днями ранее на стадионе «Авангард» (поверх нанесена цитата из его мемуаров, изданных после отставки); брошюры с полным текстом речи, которую я дополнил процитированным выше эпиграфом из Оруэлла, а также двух видео – с фрагментом выступления Хрущева и с неформальным гимном гей-движения, наложенным на изображение американского флага.

Миф может исчезнуть только под натиском нового мифа, и проект «Америка» лишь указывает на такую возможность.

Максим Шер, май 2017 г.

29 АПРЕЛЯ - 14 МАЯ / МАСТЕРСКАЯ АРТ-РЕЗИДЕНЦИИ (ЦРМ, 5 ВХОД)

29 АПРЕЛЯ / 20:00 / ВЕРНИСАЖ / МАСТЕРСКАЯ АРТ-РЕЗИДЕНЦИИ (ЦРМ, 5 ВХОД)

В Мастерской арт-резиденции «Заря» откроется выставка участника программы арт-резиденции «Заря» Николая Смирнова. Экспозиция «Мирные завоеватели», вернисаж которой состоится 29 апреля в 20:00, представит результаты работы художника во Владивостоке. Выставка продлится до 8 мая.

Проект Николая Смирнова исследует репрезентации «иностранных агентов» в культуре, перенасыщенной параноидальными образами. Как считает художник, «разрыв в масштабе между локальным и телесным, окружением и глобальными процессами, во-многом определяющими жизнь, фрустрирует современного человека и приводит к расцвету разнообразных теорий заговора, которые пытаются заполнить этот разрыв, объяснить вышедший из-под контроля мир».

Важной частью проекта станет фильм, снятый во Владивостоке совместно с учениками Владивостокской школы современного искусства (ВШСИ) по мотивам повести «Мирные завоеватели» Антония Оссендовского. Это произведение было написано известным польским авантюристом в 1915 г. с целью шантажировать немецкий торговый дом «Кунст и Альберс» (в настоящее время – владивостокский ГУМ) во время Первой мировой войны, когда повсеместно распространились «антинемецкие настроения». После издания книги Оссендовский писал Альфреду Альберсу, угрожая снять провокационный фильм по ее мотивам во Владивостоке. И хотя в итоге планам мистификатора не было дано осуществиться, сегодня эта история может получить новое прочтение. Художник снимает обещанный Оссендовским фильм в собственной, вольной трактовке, предоставляя зрителю шанс сравнить современную репрезентацию образа шпиона и «врага народа» с аналогичным образом столетней давности.

Справка: Николай Смирнов (р. 1982) - художник, географ, куратор, исследователь. Закончил географический факультет МГУ и факультет живописи МГАХИ им. Сурикова, в настоящее время студент Школы Родченко. Работает с пространственными практиками и репрезентациями пространства в искусстве, науке и повседневности. Участник нескольких десятков групповых выставок. Куратор проектов «Метагеография» (совместно с Дмитрием Замятиным и Кириллом Светляковым, Государственная Третьяковская галерея, г. Москва) и «Вечная мерзлота» (Арктическая биеннале, г. Якутск, 2016). Номинант премии «Инновация» (2016, кураторский проект «Метагеография», совместно с Кириллом Светляковым). Автор ряда исследовательских текстов, опубликованных в: «Художественный Журнал», «Разногласия», «ЦЭМ», «Городские исследования и практики». Член научных экспедиций и бывший сотрудник лаборатории комплексных геокультурных исследований Арктики (Якутск-Москва).

Вход свободный

APRIL 19 – SEPTEMBER 17

Curator: Tatiana Kudryavtseva

On April 19, the Zarya Center for Contemporary Art unveils its latest exhibition, «Materialization», which features fifty objects from twentythree young Russian designers and studios. In addition to introducing a wider publicto Russia product design, theshow seeks to weave the Far East region into the fabric of the co untry’s professional co mmunity, offering designers a platform for research into the local resources and traditional techniques of the region. The exhibition will be on view through September 17, 2017.

The objects presented within this exhibition are crafted from the most widely-used materials in contemporary Russian practice: wood, metal, stone and ceramics. Exhibition curator Tatiana Kudryavtseva proposes looking at this choice of materials as more than just the consequence of the limitations faced by the industry in Russia. In laying out the history of how these materials have been used to embody creative concepts, the exhibition touches on themes of the ecology of one’s immediate environment, mindful consumption, the ethical use of resources, and the revival of traditional techniques and local crafts.

Dedicated to Russia artists working within the mold of «designer-entrepreneurs», the exhibition explores the blending of two distinct approaches to design: design as the manufacturing of serial objects, and design as the practice of producing handcrafted goods. Knowledge of the specific properties of the materials and the ability to uncover their potential are critical aspects in transforming a concept into a quality product with its own unique look and feel. At the same time, the modern take on traditional techniques (like, for instance, working with birchbark or dairy-glaze ceramics) invests concepts with a functional purpose. This show gathers together smaller-scale furniture pieces, lighting fixtures, accessories and tableware, with the overall exhibition design developed by St Petersburg-based architects, Rhizome.

Wood, metal, stone and ceramics are four fundamental materials used by contemporary Russian product designers. In many ways their popularity is only logical: unlike hightech materials, they are easily accessible and designers in Russian know how to work with them. Over the past five to seven years, Russia has witnessed the rise of a series of notable young artists, who are not only actively participating in professional events on an international level, but — perhaps more importantly — whose works exist not only as concepts, but as actual realized objects. Given that a modern industry oriented towards the production of designer objects still has yet to take hold in Russia, the successful «materialization» of design concepts requires designers to develop the skills of an organizer and entrepreneur all in one. Objects are manufactured with the help of special studios, capable of producing limited-edition series of quality items. Several designers have even launched their own production.

At the same time, the use of traditional materials falls in line with one of the most predominant world trends in contemporary design. For those in search of «lost values» — life in moderation, harmonious coexistence with one’s environment, ecological mindfulness — the natural materials offer a counterbalance to the ubiquity of contemporary technology, which is ephemeral in nature. The recent swell of ecological consciousness incentivizes the use of materials derived from renewable resources and produced without generating harmful waste. These objects bear the stamp of personal labor, eliciting a stronger sense of ownership, which means they are also less likely to be thrown out, taking a meaningful step in the direction of mindful consumption. Within this appeal to «materiality» and mastery, particular interest is paid to the study of traditional craft. Contemporary design breathes new life into these practices, while simultaneously enriching its own expressive vocabulary, as well as our everyday material culture, reasserting local identity against the backdrop of the homogeneity of our ever-growing globalism.

Participating Designers: Olesya Ananyeva (Krasnoyarsk), Ekaterina Vagurina (St Petersburg/Moscow), Lesha Galkin (St Petersburg), Delo (St Petersburg), Anna Druzhinina (FёdorToy) (St Petersburg), Vladimir Ivanov (Kemerovo/St Petersburg), Alexander Kanygin (St Petersburg), Tanya Klimenko (Rostov-on-Don/Moscow/Pilsen), Katerina Kopytina (Moscow), Anastasiya Koshcheeva (Krasnoyarsk/Berlin), Maxim Maximov (St Petersburg), Denis Milovanov (Moscow), Yaroslav Misonzhnikov (St Petersburg), Lera Moiseeva (Moscow/New York), Nikolay Nikitin (Moscow), Darya Pavlova (St Petersburg), Ekaterina Semenova (St Petersburg/Amsterdam), Nadya Semchishina (Moscow), Maksim Shcherbakov (St Petersburg), Concrete Jungle (Vladivostok), PlayPly (Moscow), Rhizome (St Petersburg), and 52Factory (St Petersburg).

Exhibition design: Rhizome

“Materialization,” which introduces the public to contemporary works of design, will open alongside another exhibition, “Soviet Design, 1950-1980”. Assembled by the Moscow Museum of Design, this exhibition explores various aspects of the life of the Soviet citizen, as reflected in the objects of material culture. As part of the parallel program, CCA Zarya and the Far Eastern Federal University will host an international research conference dedicated to contemporary product design and the development of the discipline in Russia. The conference will be held on the campus of the FEFU, from April 18–25, 2017.

APRIL 19 – SEPTEMBER 17

On April 19, 2017, the Zarya Center for Contemporary Art will open “Soviet Design, 1950–1980.” Assembled by the Moscow Design Museum, this unparalleled project has already toured Moscow and Rotterdam, and will be on view in Vladivostok through September 17, 2017.

“Soviet Design, 1950–1980” is the result of four years spent by the colleagues of the Moscow Design Museum, parsing through the archives of Soviet designers to carefully select objects that most vividly and articulately represent the history and achievements of Russian design. Research into our material culture, the exhibition boasts more than 500 objects in total, ranging from furniture, textiles, household appliances, dishes, toys, posters, and unique archival materials.

The different sections of the exhibition each explore a specific aspect of the material culture of the Soviet citizen: the world of childhood and leisure, sports and public events, recreation and hobbies, domestic life, education, science and industrial production. The exhibition will include objects, examples of graphic and industrial design, original sketches and models from both the collection of the Moscow Design Museum and private collections, as well as unique prototypes presented by designers and their families.

Soviet designers attempted to produce objects that were timeless, long-lasting and of high-quality. The state’s assortment policy and the principles of modular design allowed them to create universal models, which could be adapted to different social and cultural conditions. This sensible, “ecological” approach became the calling card of the Soviet system of design.

As a special feature, the exhibition offers video-interviews with leading designers from the Soviet period, including Yuri Soloviev, Valeri Akopov, Vladimir Runge, Igor Zaitsev, Svetlana Mirzoyan, and Alexander Yermolayev. The show will also screen the fascinating documentary film, Design in the USSR, which was produced as a way to promote Soviet design outside the country.

In 2012, “Soviet Design, 1950–1980” first opened in Moscow’s Manege. In 2015, the exhibition traveled to Kunsthal Rotterdam, where it was met with tremendous success. After its tour in Vladivostok, the show will continue on the Art & Design Museum Atomium, in Brussels, Belgium, where it will open in 2018.

As part of the parallel program for the exhibitions “Soviet Design, 1950–1980” and “Materialization”, CCA Zarya and the Far Eastern Federal University will host an international research conference dedicated to contemporary product design and the development of the discipline in Russia. The conference will be held on the campus of the FEFU, from April 18-22, 2017.

25-31 МАРТА / МАСТЕРСКАЯ АРТ-РЕЗИДЕНЦИИ (ЦРМ, 5 ВХОД)

25 МАРТА / 19:00 / ОТКРЫТИЕ / МАСТЕРСКАЯ АРТ-РЕЗИДЕНЦИИ (ЦРМ, 5 ВХОД)

Художник из Владивостока Андрей Дмитренко представит проект по итогам участия в арт-резиденции «Заря».

Проект Андрея посвящен состоянию неопределенности, которое так характерно для молодых жителей Владивостока. Несомненной и ярко выраженной местной тенденцией последних десятилетий является миграционный отток образованного и трудоспособного населения, усугубленный портовой спецификой города, где все – временно, изменчиво, не навсегда. Поневоле у молодых жителей возникает вопрос: оставаться или последовать примеру знакомых и уехать? При этом окружающая реальность не дает однозначного ответа, и поиски направляющих движение маяков, сигналов к действию остаются индивидуальной ответственностью каждого, кто задается этим вопросом.

Метания и сомнения, характерные для общества с отсутствующими или искусственно привитыми ценностями и критериями, свойственны и самому художнику как представителю поколения молодых людей, родившихся и выросших во Владивостоке. Проект становится отражением этой ситуации и попыткой уловить сигналы – в словах своих друзей и ровесников, точно так же спрашивающих себя о своем настоящем и будущем.

ВХОД СВОБОДНЫЙ

On March 18, the Zarya Center for Contemporary Art will present a solo exhibition of the Japanese artist Michiko Tsuda. Titled “Observing Forest,” the exhibition will feature video works from the series Yeu & Mo, 2007-2009, as well as the installation You would come back there to see me again the following day, 2016.

“Observing Forest” will not only mark the first time Michiko Tsuda’s works have been shown in Russia, it will also serve as a continuation of the discussion around the representation of the concept of movement in art, put forward by “Perpetuum Mobile,” a survey exhibition of Russian kinetic art, which opened in Zarya in February.

At the beginning of the 20th century – an era under the general spell of movement and acceleration – the form in motion came into its own as an aesthetic device, whose formal possibilities would be mined and explored for the better part of the next century. A hundred years later, we have reached the point where we must now deconstruct the movement that brought about these new forms and experiences, breaking it down in basic elements that can be analyzed. The works by Michiko Tsuda offer a kind of a laboratory for the study of the form in motion and its perception by the viewer. In Tsuda’s case, this experiment is conducted on the image, on the subject matter and on the system in which these types of communications exist, all at the same time.

Tsuda’s experiments operate within two distinct disciplines: performance, for which the key moment hinges on the direct experience of the presence of the body in time and space, under a given set of circumstances; and new media art, directed towards the fixation and transmission of information (in this case, the experience of the body.)

The video series, Yeu & Mo, 2007-2009, takes its title from the exchange of elements in two images optically merged through the structural composition of Tsuda’s video work. The visitor is invited to view a video projection, showing the events occurring inside a complex installation, in which people and objects are captured by video cameras swinging like pendulums. Along their trajectory, these cameras simultaneously record and show both sides of the nearly symmetrical pavilion. The visitor is invited to interact not with the complex architectural space constructed by Tsuda, but rather with the image of that space as it appears on film. This footage is optically merged in such a way that we must negotiate a composite image that does not bring reality closer to us, but rather creates a distance between the viewer and his or her surrounding environment – a medial divide.

This divide is artificially generated with the help of the media employed and technical equipment capable of facilitating the transition of our perception of a world in motion – a world with rules governing the physical trajectory and position of an object – to a media world of distortion and interference, in which reality is not negated, but rather transformed into something virtual and inaccessible. In this sense, any movement or alteration of an image (or position, or form) of an object can appear only as a means of distancing oneself from that object. In short, any movement is a form of distance.

In this media world, the subject is primarily ethereal, something that one can absorb, but not control. In its title, Yeu & Mo revels in a slippage of individual autonomy, as the viewer begins to take on attributes of the other information directed at them. That is, they are gradually confronted with the same ether into which their body has been transformed. In doing so, the viewer must resign to a kind of optical immateriality; their body no longer solely belongs to themselves, thus rendering them incapable of warding off the optical intrusions of external influences. All semblance of privacy or autonomy is lost.

The installation, You would come back there to see me again the following day, 2016, launches an ambitious inquiry into the nature of privacy in media, but the true experience of the work is only possible through movement. Moving through the space amid Tsuda’s suspended frames, the viewer simultaneously appears within them through the use of various media, each of which adds a new effect to the situation. Within the frames, the viewer confronts their own reflection, either as a mirror as a projection from the surveillance camera. While initially this could serve as a surprise or an amusement to the viewer, they eventually grow accustomed to the idea that they are in a zone of total surveillance. It is in that moment that their gaze might “slip” into the emptiness of the frames that do not reflect the viewer, but rather offer a view of what is behind them.

What emotions do we experience when we feel a camera lens directed upon us? Even if it is filming us against our will, do we not still find ourselves performing as an object, rather than taking on the role as a subject of someone else’s attention? Michiko Tsuda’s experiments suggest that our perception of ourselves is blurred by our representation within media; but at the same time, the media field, which can appear as aggressive – the lurking threat of a forest – is nothing more than our own reflection. There is no single interpretation for Tsuda’s works, however. Just as with the dark thickets of the forest, the subject has two options: to watch or to be watched.

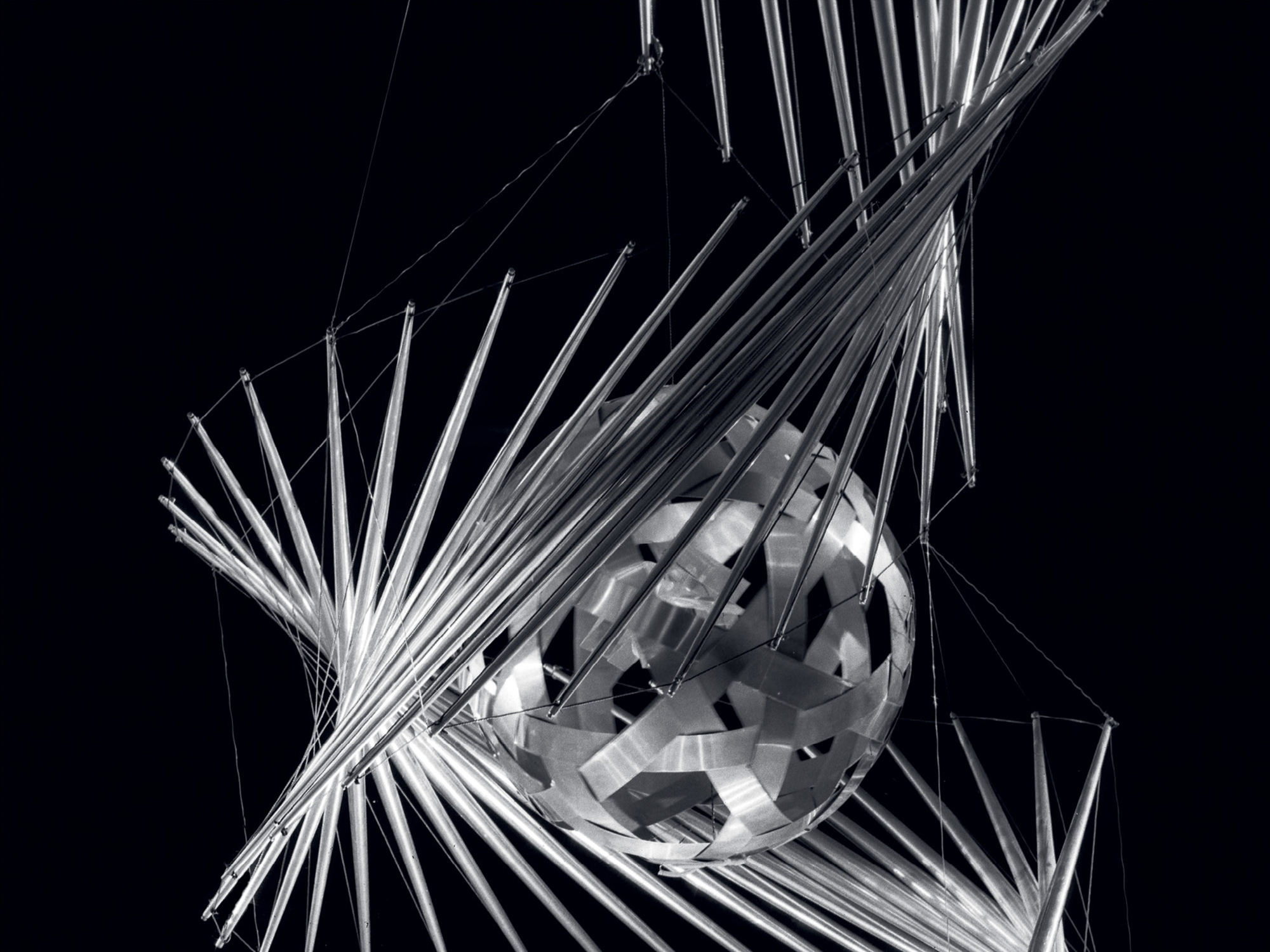

On February 3, the Zarya Center for Contemporary Art will launch its latest exhibition, “Perpetuum Mobile: Russian Kinetic Art”, a retrospective of one of the most fascinating episodes in the history of Russian art, featuring works by kinetic artists from the Avant-Garde to the present day.

“Perpetuum Mobile” embarks on an unprecedented attempt to understand the scale and significance of this movement, taking a comprehensive look at Kineticism from the moment of its inception up until today.

The contours of the relatively cohesive art historical movement known as Kinetic Art originally took form in the Western art of the 1950s. It was at this time that terms like “kineticism,” “kineticists”, and “kinetics” (all deriving from kinesis, the Greek word for “movement”) first came to be used in an art historical context. These terms heralded a new type of creator: the artist-engineer, attempting to inject art with movement, through the help of mobiles, mechanical and optical devices. The roots of this movement, however, can be traced back to the Russian Avant-Garde, working at the beginning of the 20th century.

The first work of purely Kinetic Art could be Naum Gabo’s mobile, Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave), created in 1919-1920 in Moscow. The artist’s goal with the piece was to try to advance movement and dynamic rhythm as its own aesthetic category.

Kineticism developed across disciplines, combining elements of art, design, architecture and music, while also engaging with stasis and dynamism, light and darkness, optic lenses, music, sound, and even occasionally silence. In this sense, as a movement that draws from the Russian Avant-Garde and involves multiple areas of art and culture, Kineticism proposes an incredible synthesis at the intersection of the arts, while also acting as a mirror for both technological progress and its human perception.

This exhibition reconstructs the history of the Russian Kinetic Art movement with the help of selected works from the collections of the State Tretyakov Gallery, the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, the Vladimir Mayakovsky Museum, the Shchusev Museum of Architecture, and the ROSIZO State Museum and Exhibition Centre, as well as the private collection of Mikhail Alshibaya, the personal archives of Natalya Theremin, the artist Sergei Zorin, and Andrei Smirnov, the director of the Theremin Centre at Moscow State Conservatory.

The exhibition marks the first time that the public in Vladivostok will be able to see pivotal works within the recent history of Russian art, such as the model for Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International; Léon Theremin’s termenvox(later to be known simply as a “Theremin”); the famous “cyber-flowers” of Lev Nussberg and Sergei Zorin; the self-erecting constructions and experimental stereographs of Vyacheslav Koleichuk; Boris Stuchebryukov’s Galatea, a sculpture crafted from 22,500 razor blades; Leonid Borisov’s mobiles; German Vinogradov’s installation BiKaPo; and the light-and-sound objects of SKB (“Special Construction Bureau”) Prometheus. The exhibition also includes reconstructions of works by Naum Gabo, Gustav Klutsis and Aleksander Rodchenko, as well as lithographs by El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich. Rounding out this historical survey will be a series of new commissions from contemporary kineticists.

Participating Artists:

Naum Gabo, Vladimir Tatlin, Aleksander Rodchenko, Gustav Klutsis, Kārlis Johansons, Kazimir Malevich, Ilya Chashnik, Tavel Shapiro, El Lissitzky, Tatyana Makarova, Dziga Vertov, Alexander Ginsberg, Georgy Gidony, Georgy Krutikov, Konstantin Melnikov, Léon Theremin, Solomon Nikritin, Arseny Avraamov, Boris Yankovsky, The Movement Group, Lev Nussberg, Francisco Infante, Vyascheslav Koleichuk, Sergei Zorin, Alexander Grigoriev, Galina Bitt, Rimma Zanevskaya, Viktor Stepanov, Anatoly Krivchikov, Mikhail Dorokhov, Vladimir Akulinin, SKB Prometheus, Bulat Galeev, Yury Pravdyuk, Leonid Borisov, Boris Stuchebryukov, Mikhail Karasik, German Vinogradov, Roman Sakin, Pasha 183, Dmitry Morozov, Ilya Trushevsky

Curated by Polina Borisova